Hoards I have known

For Amelia, the hoarding started small. Just a few disparate objects piled on top of her bed, seemingly chosen at random.

Then, the number of objects and their apparent randomness increased while the bed held fast as the breeding ground for greater mountains of ‘stuff’.

These Jenga-like structures comprised hard and plush toys, linen, cushions, whatever Amelia felt had that special quality, that hoard-worthy ‘X factor’. Sometimes these mountains were hidden under blankets, I suppose for safe-keeping. Who the hell knows?

The ‘point’ of this assemblage of things eluded me, but what was not in doubt was their deep importance to Amelia. She had a clear sense of purpose on hoard-making days, even rolled up her sleeves to better get on with the hard yakka this work entailed.

I did not give this new pastime much thought except to peer into her room from time to time and think, “Hmm…weird”. But the eccentricity of growing children takes on many forms and this was no more odd than a couple of other specialities like, say, chewing on a single grape for six hours or pretending to be blind (replete with ‘cane’) for an afternoon. Quirky is as quirky does.

At this early point, when she was about three, these pop-up installations were fairly temporary. Her attachment to them was shallow and fleeting. When the hoard-police (me) came to dismantle her handy-work, there was no problem and no argument. The piles of stuff had served some inner function, but she did not need to cling onto them then.

I’m not so sure when the hoarding ramped up into something bigger and, to me, more alarming. It was before the clinical suggestion of Autism Spectrum Disorder, but those words were already on my mind. Over summer, the stockpiling got bigger and its intensity ratcheted up about 100 notches.

We visited friends at their holiday house and as usual, there was a backyard gathering centred around outdoor cricket. A handful of kids aged between three and seven fought each other for their turn at the crease, but not Amelia.

She was engrossed in the creation of a makeshift hoard inside a medium-sized, red wheelie bin, the kind used to store (just store) loads of toys. Detached from the activities going on around her, she busied herself with collecting and placing arbitrary objects (not her own) inside the bin.

No amount of persuading could distract her from her core purpose. Other children, attracted by Amelia’s activity, tried to get involved but this caused her stress and she screamed at them to go away.

At my dear friend GH’s suggestion, the wheelie bin came home with us (she would not have been easily parted from it) and for the next few weeks she was its most loyal sentry. Initially, I did not allow it to come inside, filled as it was with bits of concrete, dirt and lord knows what else.

Then, the hoard-creep continued with the bin appearing one day in her room, squirreled past me like a scene out of The Hobbit (in this I’m Gollum, I suppose, and she has most definitely stolen the ring).

Her memory of the artefacts that made up the hoard was nothing less than astonishing.

If I tried to surreptitiously retrieve my husband’s wallet, this transgression was noticed immediately after Amelia had run a Terminator-like scan over her grouping of ‘treasures’. Game over.

So why was I so alarmed? I’m the first to say you should allow children to explore their needs and desires and follow their instincts, as long as they are safe and happy.

But the hoarding had no happy quality to it. For wont of a better expression, it looked to me like the play of the damned. Whatever motivated the sudden need to hoard on a grander and more intense scale – control, security, satisfaction – did not serve to connect her to the world above her eye line, least of all to us.

It seemed only to heighten her anxiety and cut her off from people in a new way; this girl we had painstakingly dragged back to us from the silence of deafness, undetected for her first two years of life.

Amelia was like the boy in The Life of Pi, stranded on a make-shift raft, barely tethered to the life boat of her family, with offers of shelter and food and comfort refused in favour of self-preservation. I felt vaguely horrified.

She could not be parted from her hoard without an epic tantrum. She wanted to sleep with it, take it into the car with her. If it remained at home, she would simply create new ones wherever she went, like at birthday parties while other children sat in a circle playing pass-the-parcel, Amelia would be in a corner safeguarding the paper. It was all so obsessive and joyless.

If I broached the subject with people, mostly they would tell me that their children did the same thing and not to worry. Really? They won’t play with others or engage in any other games or social interactions because they have to guard their ‘precious’ hoard? I wasn’t so sure.

I didn’t want to ‘break’ Amelia of this habit if it meant so much to her. The meaning of it in her life was unclear but I felt if I could help her to rein it in, reduce its importance in relation to other things, then maybe I could help her to re-engage with us, with life beyond the hoard.

The first thing to go was the red wheelie bin of horror. I offered her smaller receptacles (one at a time) for her chosen objects which she came to accept. I started asking her to collect only a set number of things to put in whatever bag or box she had selected for the day.

Thankfully Amelia enjoyed these limits and it gave her a sense of empowerment to think about what items she would choose to hang onto. Far from rebelling against the new rules of hoarding, she seemed to float back down from some obsessive place that had engaged her so intensely for months on end. It was a new day.

With this approach I was trying to say to Amelia, “Have your hoarding, yes, but calm yourself and talk to me about what you like, involve me in what interests you, give me some clue about who you are”. Basically, let me in.

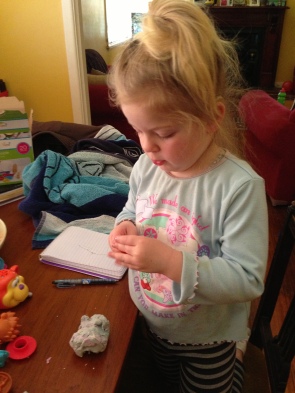

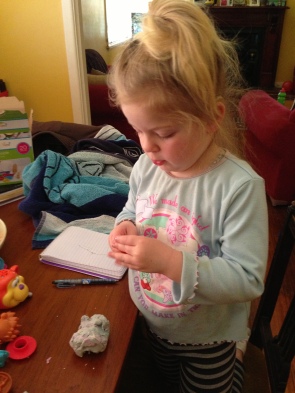

The biggest breakthrough came, as it so often does for us, with art and craft. I bought bags and bags of crêpe paper, crayons, paints, brushes, play dough, glue sticks, cardboard: all the fab stuff reserved for kindergarten storerooms. “Great, more hoardable stuff,” said my husband. I threw it all on the dining-room table and left it there all day, every day, for weeks.

If Amelia loves art (Mister Maker is like the Beatles in our house) and control in equal measure, then for a while I decided to let her have access to her favourite things, all of the time.

Suddenly, we were invited to join her for sessions of ‘making’. The simple offer of being drawn into your child’s play is not common in our experience, so it’s like the Queen has just called you up to her kitchens to bash out a lazy batch of scones. You don’t think twice, you just dive into the making.

Back in the game through ‘making’

Since then, the hoarding has not returned to its previously worrying levels of practice. It does not have that same compulsive life-or-death focus for Amelia that characterised it for some time. These days it doesn’t really seem like hoarding at all.

Like most children, Amelia still likes to carry little cases and stow secret trinkets inside her backpack, but now it’s an exercise that doesn’t dominate her life or detach her from other activities or experiences.

Because of who she is and her profound need for space and control, Amelia will always seek some alone time where her aims are her own. But now that I know I can pull her back to where we are, waiting for an invitation to play, then a little bit of ‘stash-in-the-bag’ is okay by me.

[This post was re-published here by mamamia.com]