IN THE wonderfully acerbic political TV series, The Thick of It, there’s an episode involving a ‘Super Schools Bill’, which proposes the closure of special needs schools across the UK. The hapless cabinet minister who must argue in favour of this integration agenda is Hugh Abbott (Chris Langham).

IN THE wonderfully acerbic political TV series, The Thick of It, there’s an episode involving a ‘Super Schools Bill’, which proposes the closure of special needs schools across the UK. The hapless cabinet minister who must argue in favour of this integration agenda is Hugh Abbott (Chris Langham).

In this, Hugh is faced with a moral conundrum. He doesn’t agree with the Bill and his senior special advisor, Glenn Cullen (James Smith), has a son who attended a special needs school and flourished there. It’s a personal thing.

Glenn’s catchphrase to sum it all up is simple: ‘Inclusion is an illusion’.

But poor old Hugh doesn’t have the luxury of holding to a thing like principles when it comes to matters of state. Instead, he is forced by the government’s pitbull-esque director of communications, Malcolm Tucker (Peter Capaldi), to support the Bill.

In doing so, Hugh betrays his own beliefs and sells out Glenn and his son by using their personal story to argue for the closure of special needs schools. All in a day’s dirty work for the Secretary of State for Social Affairs and Citizenship.

Inclusion is an illusion. I hadn’t seen this episode for a while but I was suddenly reminded of Glenn’s line last week when I made a foolhardy call to a local activity centre to ask about my six-year-old daughter Amelia joining one of their classes.

Early in the call I volunteered the information, as I always do, that she is deaf and autistic, to be clear about her needs and advance the conversation about how best to include her.

For a minute it all sounded pretty positive. The centre had a separate class for children with ADHD/ASD with an Occupational Therapist on hand for support. Great, I thought, that might be better for Amelia than the regular classes, at least to begin with.

But I was misguided in that momentary feeling of positivity. Amelia, it turns out, would not be eligible to attend either kind of class. The doors I had hoped to open for her swiftly closed, one after another.

About her deafness, I was asked how far background noise would impact on her ability to hear. This was not so the noise could be controlled or limited in some way. It was to point out how the environment would not be ‘appropriate’ for my daughter.

I hurriedly explained that while Amelia is deaf, she wears hearing aids, can speak quite well and follow most instructions and that I wasn’t expecting anyone to be a fluent Auslan interpreter for her. I just wanted them to know that standing near her and making sure she could see the face and hands of people speaking would help her understanding of any directions in the class.

But her deafness turned out to be a deal-breaker for this centre. They could not be convinced that it wasn’t an insurmountable barrier to Amelia’s inclusion in the program.

To me, it’s simply a fact about her that requires a little effort to understand and accommodate. After that, she’ll do the rest because she’s tough and ace and super adaptable.

I know that people don’t often encounter deafness in their day-to-day lives, but there’s an unsettling ignorance that surrounds its understanding in the broader community.

It’s unpleasant to confront this as the parent of a deaf child, but there’s a spectrum of misunderstanding that at its lower levels assumes that it is ‘too hard’ to communicate with a deaf person (so we won’t try).

At the extreme end of this spectrum reside the people who mistakenly believe that deaf people are somehow restricted in their intellectual capacity. ‘You don’t communicate the way I do, so I see you as lesser than me’. Not different, but reduced.

Then I was asked if Amelia attended a mainstream school – the children in the special needs class all do apparently. Well, no, I replied, she goes to a school for deaf children. Then I was asked a theoretical question, about how Amelia might cope in a mainstream school.

How to answer something like that when she has never been schooled in a mainstream environment? That’s when my agitation, which had been like a worrisome tickle at the back of my neck from about the four minute mark of the call, really started to ramp up.

My pulse had quickened and a slight tremble rippled across my arms, my back, like a warning on the surface of my skin.

As the call neared its conclusion, I realised that it didn’t really matter what I said to the person on the end of the line. Every answer I gave presented yet another obstacle to Amelia’s inclusion. Another reason to say ‘no’.

Instead of answering questions about how they might help, I felt as though I had inadvertently participated in a survey about all of my daughter’s faults. It made me feel sick.

This had honestly never happened to me before, so I was more than a little shocked. Most places in my experience will try and meet you and your child somewhere in the middle, somewhere fun and safe where everyone’s needs can be met.

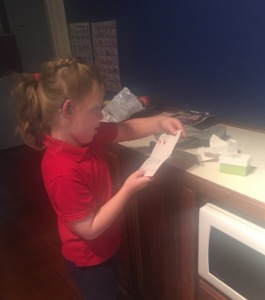

Hamming it up at the St Martin’s Youth Arts Centre (2013)

The St Martin’s Youth Arts Centre invited me to sit down with them for an hour to learn all about Amelia and how their programs could work best to include her fully.

The Northcote Aquatic and Recreation Centre has hired an Auslan interpreter so that deaf kids like mine can access swimming lessons in the only language that’s going to cut it in the pool. They also committed to one-on-one teaching when they were informed of Amelia’s autism.

Just a few cool examples of how NOT to alienate small children and their families.

The person from this centre gave me nothing, no extension of flexibility or sensitivity, just an empty offer of ‘wait-listing’. Our case was lumped casually in the too-hard-basket, and that, as they say, was that. I hung up mid-sentence, mid-sob as the rising lump in my throat betrayed me and echoed its hurt down the line.

But I couldn’t just leave it at that. I was still shaking as I sat down to write the centre a message of ‘feedback’. I’m not interested in disclosing who they are because I just read Jon Ronson’s important book about public shaming and it’s an unedifying road that will serve no grander purpose.

I will, however, share my emails (names redacted) here because I think it’s vital to show the true cost of these negative interactions, where inclusiveness was hoped for but in reality denied to a child with special needs:

Email # 1

Hi there, I called today to see if my 6 year old daughter who is deaf and autistic could come and try some redacted classes with you. She loves to redacted and I thought it would be good for her physical and social development. I was told that she is not eligible for either redacted or the redacted because of her special needs. It is pretty devastating to have your child turned away from fun activities on the basis on her disabilities. It’s great that you have the redacted group for ASD/ADHD kids but apparently my daughter is not eligible because she goes to a special needs school for deaf children. So you cater to special needs kids, just not my kid? I find it hard to understand. Amelia has participated well in programs run by places like St Martin’s and they welcomed her with open arms. She is a lovely, bright girl who has challenges but always benefits from new learning environments. I’m really disappointed – you have no idea how awful these kinds of experiences are for parents like me. Thankfully, most places operate in the true spirit of access and equity. Thanks for taking the time to read this feedback. I hope that other kids might benefit from this, even if my daughter is not welcome at redacted. Sincerely, Melinda

I did receive a quick response, but it was pretty cold and informal, sticking hard to the company line. In summary, they understood how ‘frustrating’ it must be for parents like me, but they just couldn’t accommodate Amelia right now.

Frustrating? Like when you can’t get your car started in the morning or you miss a train? Yeah, I don’t think so. That inadequate word inflamed my anger even further, so after a few hours of grumbling around the house and chewing the inside of my mouth to shreds, I emailed them again:

Email # 2

Hi redacted,

Thanks for responding to my email. I guess I am expressing more than frustration and the reason for that, whatever your company’s capacity to deal with different needs in children, is that you wrote off the idea of Amelia joining in on the basis of very little information. I said ‘deaf’, ‘autistic’ and ‘deaf school’ and after that it didn’t really matter what that means for Amelia in practice and how far she might be able to participate with only a little bit of prompting.

You concluded that her needs were more severe than is currently accommodated within your programs, and I just can’t accept that that’s fair. I would have loved it for instance if you had suggested that I bring her in to meet someone from redacted to get a sense of her, and then decide if she needed to be waitlisted for some other kind of program. The deciding factor of Amelia being in a ‘special school’ – and I’m not sure that a deaf school fits within that category – is a strange one.

There are plenty of ASD kids who attend mainstream schools but they often need at least some in-class support to do that. Amelia goes to school without the need for any extra help at all. She works on the same curriculum as every other child in the state, the main difference is that she learns bilingually, in Auslan and in speech. To me, it makes more sense, and is far more equitable, to assess the actual needs themselves, not which school system has been chosen by parents as the most appropriate for that child for a whole range of reasons.

Obviously, I wish that you had handled my call with a bit more of an open mind and frankly, a bit less ignorance of how special needs children function inside and outside of mainstream/special schools and programs. I have never been told that Amelia’s needs, such as her deafness, make her ‘too hard’ to deal with, which is the real way of saying ‘we can’t appropriately cater to her needs’. I mentioned them to you mainly so that her instructor/s would have enough information to be sensitive to those needs in practical ways, like making sure she could see the person speaking, and so on.

You would be surprised just how resilient and adaptable a child like Amelia with her unique set of needs can actually be.

Regards, Melinda

Amelia, signing to her swimming teacher (2015)

Now I felt better, as though I’d fully advocated for Amelia even if the result was still the same. I might not always be able to knock down the walls that get in her way, but goddamn it, I will always let people know when their stupidity and heartlessness has let us down.

Soon after, I got a call from the company owner and we actually had a good chat about how to properly include someone like Amelia in their activities. It was the conversation I’d expected to have at the outset.

And this person apologised, saying those magic words, ‘I’m sorry that you had such an upsetting experience’. It didn’t dissolve my afternoon of distress, but I did appreciate it.

By this stage though, I wasn’t looking to convince them to let Amelia join in – I don’t want her anywhere near a place that takes such an appalling view of her needs – but I did want the owner to understand what might have worked better in our case. How they might handle future Amelias.

Like, if they had just invited us to come in for a short meeting, we could have had an open and honest discussion about the best kind of class for Amelia. They could have met her rather than judging her abilities over the phone.

Maybe we would have decided mutually to come again at a later time, but really, we’re not solving world peace here, are we? We’re just talking about letting a little girl try something on for size to see if it might have fit.

Instead, they closed their minds to her sight unseen, which is a great shame. Because Amelia’s such a fabulously fun chick, so interesting and full of whimsy. Some people regard her as an asset to their groups, even a leader. This centre will never know her and it’s one hundred percent their loss.

Barriers to access are real and they do hurt. Take note people running programs for kids: pump up your heart valves and have a think about how your special needs policies impact on people who are already doing it pretty hard.

We’re all a part of the same community and when we feel brave enough to step out of our houses to have a go at something new, please hold our hands instead of turning us away.

Inclusion doesn’t have to be an illusion, and you might find that instead of a child being ‘too hard’, they will teach you something priceless about what it means to be alive.

Amelia finally came home and I greeted her with the news falling urgently from my lips, “Baby, M left you a present, it’s inside!”

Amelia finally came home and I greeted her with the news falling urgently from my lips, “Baby, M left you a present, it’s inside!”