Kicking back and growing up

THIS WEEK in my house we will celebrate in our own small, quiet way that modern event known as Mother’s Day.

For us it still feels like a new tradition and this year will mark the sixth time I will be lucky enough to be in the box seat for a hand-made card from my daughter Amelia, followed by burnt toast served on a large hard-back book (Bowie: Album by Album) in bed.

Oh, the luxury.

I get that it’s a super commercialised ‘holiday’ and that the marketing of Mum-gifts is so narrow in its view that it can only imagine one uber-domesticated, goddessy-type mother.

The reality of my childhood is that if you were going to buy power tools for anyone it most likely would have been my Mum (sorry, Dad).

I can’t get overly energised about public perspectives on what is actually a very private role. It belongs to no-one except the woman who is doing the mothering and the child or children who share that relationship with her.

Mother’s Day is about business; but my sense of motherhood is nobody’s ‘business’ but mine.

It’s such a complex thing to me, being a mother. It has meant so many different things over time, I can hardly begin to unthread one from another. It’s a tangle of feelings, thoughts and experiences. And so many ups and downs.

Even before Amelia was born, I felt strangely detached from the idea of motherhood. Her conception occurred in a medical laboratory; her little egg was extracted from my body while I was unconscious, fertilised in a test tube. My husband and I didn’t even need to be in the same room for that.

I was technically present, but I felt far, far away from myself, like waving to a familiar shape on the horizon who doesn’t see you.

Pregnancy helped to repair that detached part of me, at least back then. It fused splintered bits of my self back onto the bone. Whatever interventions I endured before and after Amelia’s birth, carrying her inside me drew me closer to her, to the nurturing experience of almost-motherhood.

My body was not just some broken machine that required drugs and procedures to work like it was meant to. It was life-giving, sustaining another person’s growth. Every kick, lurch, forward tumble (what the hell was I growing in there, an acrobat?) inside me was a sign that my body was finally doing its job.

I could pause my lifelong hatred of it and welcome its changes for the first time.

My take on childbirth is mostly a pragmatic one. It’s a necessary means to an end. Of course there were more medical interventions, more body-numbing drugs, incisions. I could not escape them, but they did not sever me from the powerful emotions I felt upon seeing Amelia for the first time.

And she was perfect. She really was. My January girl, Amelia Isobel. Named in part for a forgotten woman we wanted to remember through the gift of our daughter.

The distance we had travelled to get there, to reach each other, was long and hard. Yet we had made it and contentment washed over me like warm water moving downstream.

It turned out that the perfection we swiftly projected onto Amelia was illusory. Nobody looks at their baby and sees anything other than all that is right and true.

But there were shadows all around. Third parties. Autism was like another child born alongside Amelia, standing between us. It held out its small hands and shouted, “Stay away from me!” It kicked and railed and screamed and it never let up.

Deafness too. Before we knew it was there, deafness was another character vying for attention in an already confined family space. The cost of not knowing that its presence had stood in Amelia’s way for two years, causing us to wonder why our child felt so remote, remains with me.

That grief grows smaller but it never leaves.

Amelia’s unique set of challenges have tested to the hilt the ways I see myself as a mother. What it means to love a child who did not hear my voice after she was born and who could not really bear for me to hold her close. Who sometimes seemed to reject my very existence in relation to her.

How can I be a mother if I can’t comfort my own child? Show her my love through the warmth of my body, the song in my voice?

The years have been challenging and arduous. I will not deny that for a number of those years I have felt like the living embodiment of The Wreck of the Hesperus; a walking tale of woe.

I have been a mother in name, it is true, and I bear the massive responsibility of guiding a very vulnerable person through the mists, onto dry land. But it hasn’t really penetrated beneath my skin, my sense of really being Amelia’s mother.

In our darkest years, mothering her meant learning and then teaching her how to sign before she could talk. I worked hard to give her language and access to the world, painstakingly, word by word.

I watched her tear herself and the house apart in the midst of yet another distressing meltdown. I tried everything and achieved little save hours and hours of sobbing. For us both.

We couldn’t go on outings or share in the most basic things like a walk together for the longest time. I would watch ‘normal’ mothers on the street from my car, talking and chatting to their little ones. So effortless, it seemed. I thought my heart might break in two.

For me motherhood exists in those incidental spaces where small exchanges of love seem possible. Long, soft cuddles on the couch, whispered secrets at the park, tears wiped away with the palm of my hand. All are welcome.

They’re spontaneous, shared events of connection and they combine to build into a bigger picture of mother-daughter bonding.

It is simply a fact of Amelia’s early life and the severity of her challenges then that she couldn’t bond with me in traditional ways. I understand now that she did love me and need me, just not in the ways I had expected.

She couldn’t show me and I could not see it or feel it, but her love was there, as was mine. It just took us some time to see each other properly.

In my own narrow view of motherhood I had set us both up for failure. I feel very sorry for the pain I inflicted on myself then and the distance that created between she and I. I held her in my mind as though on a string, floating away from me, when I should have tethered her closer still.

Because now she is six and though I feel like I have waited for an eternity, Amelia is really ready to love me, in her own, quirky way. I’m doubling down and keeping her all for myself.

Daily, hourly, she throws herself with gusto into my arms and says earnestly, “I love you Mummy, you’re my best friend in the whole wide world”. I am now a mother who feels ten feet tall. A world beater; life conqueror.

I am learning to trust in these moments, rather than unpack them endlessly or worry that my girl is faking it just for me.

You know he’s wishing that was a fried pork dumpling

On Sunday we ventured out for lunch in a rare attempt at family ‘normality’ and it was one of our most wonderful days so far. Top five, I reckon. We ate dumplings like

Friar Tuck would have if he’d been lucky enough to have a yum cha local to him in Sherwood Forest.

We ate together, we laughed. Amelia sat happily and I actually relaxed. We left and went in search of ice-cream; there was no hurry, we could take our sweet time. Amelia sat patiently on a stool next to me while we waited for her Dad to purchase a messy chocolate concoction in a cup.

And then we walked to the lights on the corner to cross to our car. I stopped and leaned against the light pole. In front of me, my dear little person leaned her body back into mine.

It was a subtle movement, but the pressure of Amelia resting on me, the warmth, was a heady mixture. I took a risk then. I reached up my right hand to stroke her beautiful, blonde hair.

She let me, so I grew bolder. I ran my hands through it, letting the strands fall down her back like it was the most glorious silk in the world. As a mother I’ve only ever wanted to be able to show such tenderness to my child.

She didn’t pull away and I didn’t breathe.

The extravagance of being able to have this contact without rebuke was everything to me in that moment. I looked up at the people in cars idling on the street and thought “I wonder if they look at me and see a mother?” Because that’s how I felt right then. Like a real mother.

It’s a new feeling, like a shiny coin I’m turning over and over in my hand, marvelling at the shapes, the grooves I can see in the light. I know I will feel it again and more often and that thought is more exciting than a thousand Christmases at once.

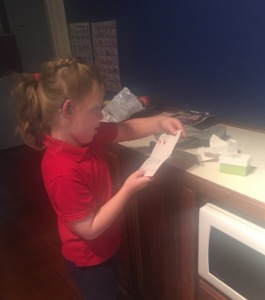

Yesterday, Amelia jumped off the bus from school clutching a plastic bag behind her back. Ah, the Mother’s Day stall at school. She’d spent the $5 I gave her that morning and was clearly pumped about her acquisition.

She ran swiftly ahead of me to hide my present under her bed. Last year she would have just shown me, but she’s learning how to harbour secrets and cherish surprises.

And I don’t care if that bag has a tea cosy in it, a weird tissue box holder, or a garishly decorated mug to add to the 400 others in our cupboard.

It’s Mother’s Day on Sunday and I want my card, my burnt toast and whatever special prize my beloved daughter thought to choose just for me, her mother and her best friend in the whole wide world.

Amelia finally came home and I greeted her with the news falling urgently from my lips, “Baby, M left you a present, it’s inside!”

Amelia finally came home and I greeted her with the news falling urgently from my lips, “Baby, M left you a present, it’s inside!”

SHE ONLY let go of his hand for a moment, all the better to chase the colourful kite sailing above their heads. Her arms are raised, as though she can touch the clouds or pull the kite to her with an invisible string clasped in her hands.

SHE ONLY let go of his hand for a moment, all the better to chase the colourful kite sailing above their heads. Her arms are raised, as though she can touch the clouds or pull the kite to her with an invisible string clasped in her hands. WE WERE at dinner with friends when I saw the bonny baby at the next table. A new-born covered in a light muslin wrap, protected from the too-cool air inside.

WE WERE at dinner with friends when I saw the bonny baby at the next table. A new-born covered in a light muslin wrap, protected from the too-cool air inside.